This week’s Song of the Day curator is composer and thereminist Dalit Warshaw! Dalit is also performed with NYFOS this week in

This week’s Song of the Day curator is composer and thereminist Dalit Warshaw! Dalit is also performed with NYFOS this week in

our concert From Russia to Riverside Drive: Rachmaninoff and Friends.

from Dalit Warshaw:

…And More About the Vocalise…

As the player of an instrument that shines when exhibiting expressive and expansive melodic line, and as a Neoromantic composer who probes the role of melody pretty much daily, I feel compelled to readdress the idea of the vocalise.

The vocalise, a form originating in the 18th century to connote a “chanson sans paroles” (song without words) and pioneered by composers such as Lully and Rameau, has evolved since its original role as a pedagogical vocal etude. By the early 20th century, the vocalise largely came to mean a vocal and orchestral interlude in the midst of dramatic scores.

It has been an oft-seen goal of composers within the past 100 years to address the past in order to redefine it and bring it into the present, first seen in the efforts of Schoenberg and Stravinsky in their different versions of Neoclassicism, and more recently in the various ways that Neoromantic composers tip their hats to past forms through quotation or pastiche. While variation and sonata forms (and their offshoots, such as symphony and concerto) have experienced (and endured?) their share of exploration and reinvention, it is interesting that the vocalise has not joined their ranks in being transformed within a contemporary context. While the vocalise has found its way into jazz and world musics as the vocalese, it is rare to hear a vocalise written within the last 50 years.

Why might this be? A theory could be that, with the decline in the prominence of melodic line in music composition within the last century, and an increased focus on more motivic and textural writing, there was no room for the vocalise to undergo a transformation while keeping its fundamental long-lined character.

Embarking on a short hunt, I noticed that the results are mostly limited to pre-1950. Faure’s haunting Vocalise-Etude was written in 1906. Stravinsky’s Pastorale was written in 1907, its final revision published in 1933. Rachmaninoff’s aforementioned Vocalise was written in 1912. David Diamond’s Vocalises for soprano and viola was written in 1935. Villa-Lobos’s Bachianas Brazilieras was written in 1938. Some notable and very beautiful exceptions are George Crumb, Vox Balaenae, Vocalise (1971), John Corigliano’s Vocalise (1999), and Andre Previn’s Vocalise (1995).

Speaking for myself as a composer, while melody must always be at the structural core of my work, whether it be palpably or ambiguously represented, its presence has often taken the back seat to harmony and motive, in this way continuing perhaps in the legacy of Debussy. Every so often, however, I feel I must prove my allegiance to melody in a clearer capacity, either in a need to simplify, or to test how uniquely I can personalize this art so weighted with the shadow of past masters, and so easily perceivable as cliché. How to redefine melody in a way that maintains its properties and yet does not sound derivative?

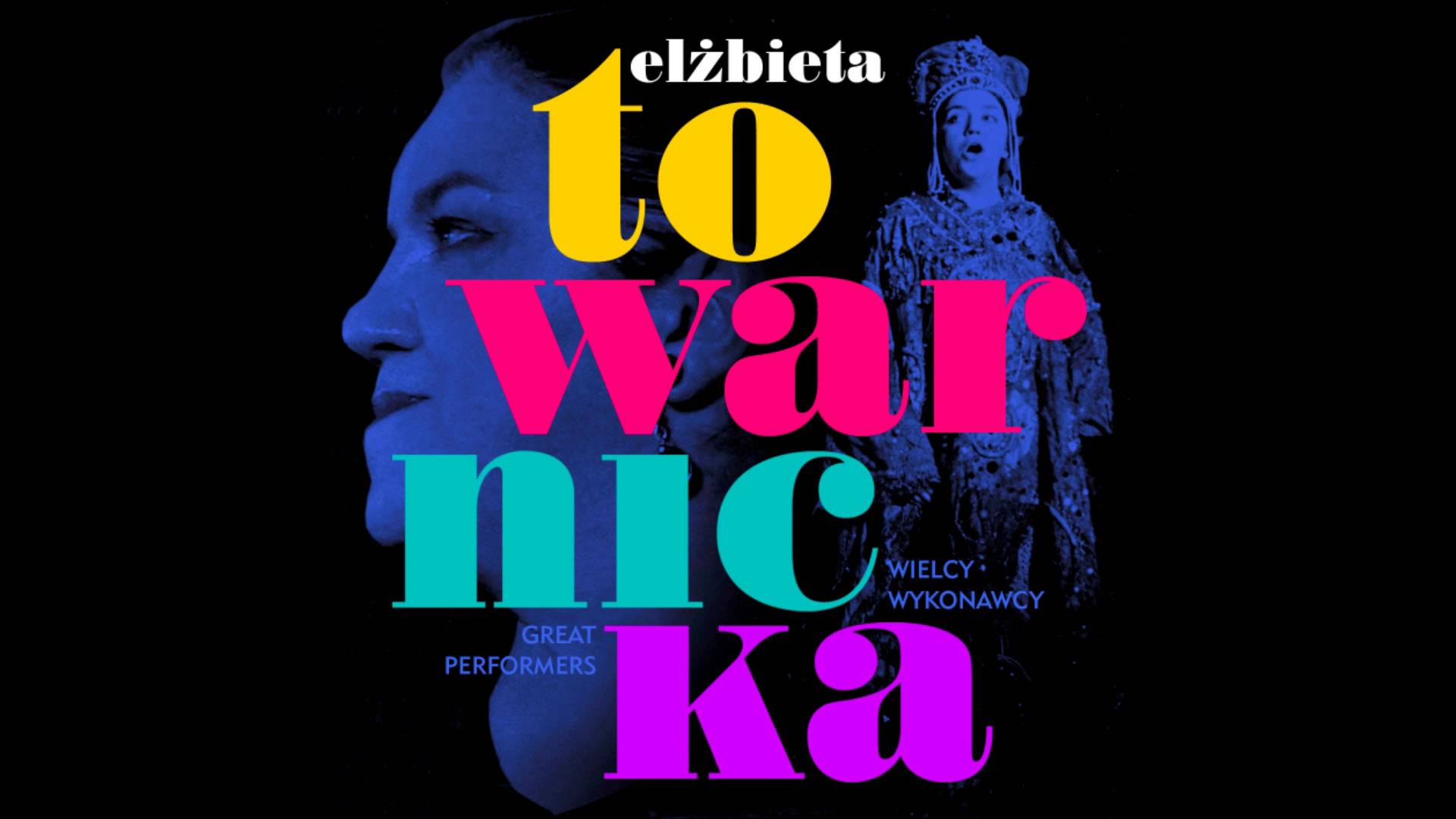

Alas, I shall leave this question open. In the meantime, I present for you the Vocalise-Etude of Karol Szymanovsky (1928), performed with a dark yet wistful expressivity by Elzbieta Towarnicka, soprano, and Maria Rydzewska, piano.

0 Comments