When I was planning the FSH gala with Amanda Bottoms and Dimitri Katotakis, they both mentioned that they’d recently sung “Too Many Mornings” from Sondheim’s Follies. For some reason, I initially resisted. Too hackneyed? off-topic? I don’t know. About two weeks later I woke up and changed my mind. I am glad I did.

When some people retire, or win the lottery, they run around the world seeing productions of Wagner’s Ring Cycle. Were I in that situation, forget the Ring. I’d see every production of Follies I could. It is a fascinating work, elusive, difficult to get right, filled with great songs and complex characters. I admit I am slightly obsessed with it. It is the only musical that replicates Proust’s strange, amorphous sense of time in Remembrance of Things Past. In both works you can’t really tell when any of the scenes take place, or how long they last in real time. Follies starts and ends in a conventional theatrical realism as a group of vaudeville-revue performers gather for a final reunion in their old theater which is destined for demolition. But as it progresses it enters the world of dreams: intense, symbolic, haunted. Real time ceases to exit. Emotional time takes over.

The characters of Follies are shadowed onstage by their ghosts, who are lit differently and dressed in black and white. They enact the dramas that continue to drive the the protagonists of the show, a pair of married couples. These ghosts haven driven them in bad directions—to despair, to fantasy, to infidelity, to emotional numbness. In “Too Many Mornings,” Ben (now a successful businessman) and Sally (now a needy, lonely housewife) seem to rekindle the romance they had when they were young. They are both in unhappy marriages—Ben chose the cooler, more worldly Phyllis as his trophy-wife, and Sally settled for Buddy, a traveling salesman. But for the space of this duet, their old ardor returns. Sally seems to remind Ben of the idealistic, hopeful man he once was. And Ben has been Sally’s dream ever since he dropped her to marry her best friend.

Sondheim’s music tells two stories. It surges like Puccini—a rare burst of full-throated, red-blooded romanticism for this usually acerbic composer. But in the interludes and chord progressions we hear hints of confusion and disassociation, the outer edges of madness. In about ninety minutes Ben will have a complete nervous breakdown, leading to the final reconciliations. In “Two Many Mornings,” Sondheim lets you feel the germ of his collapse.

And the staging completes the underlying story—at any rate, the staging I remember from one particularly moving production. During the course of the duet, Sally’s ghost entered and stood between the present-day Sally and Ben. We realized that his passion wasn’t for the love-sick, middle-aged woman whom he held in his arms. It was for his memory of her as a very young woman—and his memory of himself before he sold his soul to Mammon. Over the violin solo in the postlude, Young Sally slipped away. As Ben confronted the real Sally, his desire for her evaporated. All of this eluded sweet, delusional Sally, still convinced she would finally be reunited with the love of her life.

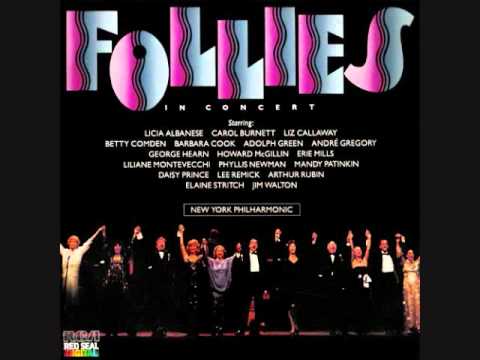

George Hearn and Barbara Cook

0 Comments