When I was sixteen, I began taking formal voice lessons in Philadelphia. I found a teacher via a wonderful book on Mario Lanza I received for my birthday. I had just recently discovered him and was inhaling every book and record I could get my hands on. In this particular book, there were a number of testimonials from people who knew Mario, worked with him, or were inspired by his voice. One of these was written by Enrico Di Giuseppe, a wonderful tenor who enjoyed a long and productive career with the Metropolitan and NYCO from the 60s-80s in a variety of roles. At the conclusion of his chapter, he stated that he was teaching voice privately in Philadelphia. Inspired, I wrote him a lengthy letter requesting lessons. He called me one evening and we set up a trial lesson for that week. I brought him ‘Amor ti vieta’ from Fedora because “it’s short and only goes to an A”… his reaction was pretty priceless. After I bellowed my way through the aria like the sixteen year old baritenor I was, he handed me the “24 Italian Hits” and we started working together. He was my teacher for the next six years until his passing and in that time, he became very much like a grandfather to me.

A few months into my lessons, I told him I was studying German in high school. His eyes lit up and he leapt from the piano and over to his bookshelves. He handed me a couple books to take home and begin studying: they were Schubert’s ‘Die schöne Müllerin’ and Schumann’s ‘Dichterliebe’. I fell in love with them immediately. To this day, the music of Schubert brings back beautiful, simple memories of driving to and from lessons in South Philadelphia in the passenger seat of my mother’s car, or traveling around Germany in the summer of 2001 as an exchange student. It may seem strange that a teenager who was in a rock band and played sports had Schubert as the soundtrack to his high school years, but the music is inextricably linked to some very special moments that shaped who I am today.

I put German lieder aside for a number of years, focusing instead on standard operatic arias and American art song. When I moved to Europe to start my career there, the music understandably made its way back into my life. My first assignment as a member of the Young Singers Project at the Salzburg Festival saw Herr Schubert make a return. A year later, when I joined the Junges Ensemble at the Theater an der Wien in Vienna, it was Herr Schumann’s turn. Each ensemble member was tasked with planning a full-length recital. I chose to sing ‘Dichterliebe’ for the first half. When I first studied this cycle, both my musical and German skills were not quite mature enough to comprehend the depths of these songs, each of them individual masterpieces. I remember exactly where I was when I translated the texts for the first time. I sat in a Starbucks a few paces from St. Stephen’s cathedral, slowly approaching the final song of the cycle. I remembered learning it in high school, but dismissing it as another ‘wimpy’ song where the narrator is again whining about his profound pain. This time, I listened intently. I thought about everything that had preceded this song, not just textually, but also musically.

Die alten, bösen Lieder. Die Träume bös und arg. Die laßt uns jetzt begraben. Holt einen großen Sarg

All of the old songs and dreams. Just bury them. And that coffin?? It’d better be %#$&@ huge..

(that’s an “Andrew translation”, mind you)

The narrator goes on to specify that the coffin should be as large as the great Heidelberger Fass, a massive wine vat located in the cellars of the Heidelberg Castle. The death bier upon which it should be placed must be longer than the bridge to Mainz. And to carry it, fetch no fewer than twelve giants, each of them with the strength of St. Christopher. They should drag it out and sink it deep into the sea, because a coffin of this magnitude deserves such a grave.

The music at this point just collapses into a slow and brooding pace. It’s as if the narrator has reached the height of his anger and frustration and smashed a mirror with his bare fist. He now stands completely still, catching his breath, and we get the kicker..

Wißt ihr warum der Sarg wohl

So groß und schwer mag sein?

Do you know why this coffin is so damn heavy and large??

It’s set deep in the range of the singer, be it a baritone or tenor, almost to forcibly prevent him from singing this hushed section too loudly or forcefully. Then the vocal line leaps up an octave, as the narrator just sinks to the floor crying. Mind you, this is not a loud, ugly cry.. this is an eyes-squinted-shut, mouth-agape-but-no-sound-coming-out cry here.

Ich senkt’ auch meine Liebe

und meinen Schmerz hinein…

I sank along with it my love and my pain…

I sat in that Starbucks, covered my mouth with my hand and, contrary to the narrator’s experience, actually DID ugly cry. Even in rehearsals, my voice broke every single time I came to this final phrase, and at the performance, the ‘-ein’ of ‘hinein’ did not even phonate. The most challenging part of the entire cycle was keeping completely still during the absolutely beautiful piano postlude that follows.

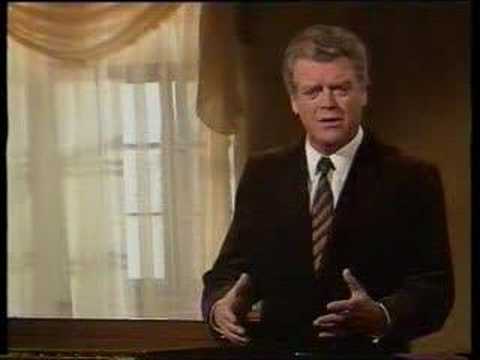

So this lengthy post is basically to tell you that today’s song is ‘Die alten, bösen Lieder’, the final song in Robert Schumann’s ‘Dichterliebe’. I’ve chosen the wonderful Hermann Prey, in a video performance of the entire cycle made late in his career. Though past his vocal prime, Prey does a remarkable job conveying the emotions I described above. He embraces the silence and stretches out those final phrases, really twisting that knife.

Hermann Prey

0 Comments