I grew up surrounded by song, most prominently at the feet–or the fingers– of my grandmother, who lived next door. ‘Grandmere’ grew up in early twentieth century Jewish Harlem, and her youthful and lifelong joy was the musical theatre. Every family gathering included singing around the piano as she played from her boxes of sheet music dating from 1910 on. (There were ten songs from South Pacific alone). So, as I embark on this week-long project, which, of the hundreds of songs I love, do I begin with?

A couple of weeks ago it occurred to me that ‘everything I know I learned from the ‘AABA’ song’–the thirty-two bar form that the great American songwriters of the early 1920’s created–Kern, Rodgers and Hart, Gershwin, Porter. Basically, the form uses a title or sentence that generally repeats in the three A sections; the B section or bridge takes you in a different direction, before a recapitulation. The great AABA songs are mini-essays exploring longing, desire, flat-out expressions of love, unanswered questions, moments of being (think ‘All the Things You Are’, ‘Yesterday’, ‘If I Loved You’).

I googled the AABA form, and found that the analytical template was Irving Berlin’s ‘What’ll I Do?’ Berlin seems like a perfect place to start for me…so many of those songs we sang at my grandmother’s house were by this immigrant saloon boy who became the quintessentially American songwriter. One of my earliest musical-going experiences was seeing a no-longer-spring-chicken but still belting Ethel Merman in Annie Get Your Gun in the mid-sixties. (Her voice still rings in my ears!).

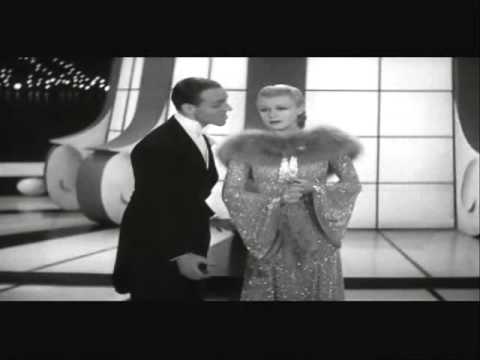

Today’s song is Irving Berlin’s gorgeous ‘Let’s Face the Music and Dance’. It is Irving Berlin in a haunting mode, a hortatory response to troubled times. It also has one of the greatest music videos ever (in that it was written for an Astaire Rogers film, Follow the Fleet). Writing for Astaire made Irving Berlin jazzier and more ‘sophisticated’; legato and syncopation play with each other. He opens with the long-ish rise and fall of the sentence “There may be trouble ahead”, followed by the shorter exhalations of “while there’s moonlight–and music–and love and romance”, and concludes each verse with the solid title statement. Astaire sings with his whole body, and it is as if Irving Berlin is writing with that physicality in mind. The sequence in the movie is about eight minutes long, so you might want to skip the ‘play within the movie’ attempted suicide set-up and get right to the song…as Cole Porter wrote “You’re the top, you’re a Berlin ballad!”

Lee, Lucky you to have been brought up around so much singing. Thanks for sharing. I look forward to more!

Lee Stern’s essay is wise, inspiring, poignant, authoritative, original, and as memorable as this very song he writes about. He is the ideal person and authority to be writing about the great American songbook—and all songs and music. I can’t wait for his next post.